Rihla/رحلة:

a Classical Arabic term of a quest, or a voyage undertaken for the sake of divine knowledge of Islam.

When I tell people about my dissertation topic [formally, ‘Representations of Istanbul as the Juncture Between Islamic and Christian Worlds in Early Modern Travel Accounts’], they look at me with a mixture of confusion and boredom—and I get it because yes it seems like writing an extended essay on maps of renaissance Istanbul seems like something a Geographer would do and very much not an English Literature student, and yes, why do I care about a city half way around the world? But this project, which should not have but has taken up the majority of my brain space since maybe June, really is the culmination (it is nowhere near finished) of an amalgam of thoughts, feelings and impulses; some of which have whispered to me since childhood and some which have become alarmingly loud since I’ve started this degree.

When looking at travel, in my mind I convert it into a form of escapism. Not the type of escapism of oh-my-god-the FBI are after me, I need to hide out in a small town in Cambodia, nor the idea of a permanent migration with flashing images of a sterile second-rate airport and the sour taste of leaving everything you’ve ever known behind. For me, never discounting the privileges I have of being able to travel the world at my own leisure with the backing of a ‘bloo’ passport, and a mother who wants to leave the UK almost as frequently as I do, travel is as much about the experience of going-somewhere-else as the location itself. It’s about removing myself from my mundane every day, its conjuring new lives and histories and identities. It is supplanting myself into a life that could never be mine but just imagining it for a second.

And I think this is why I spend my holidays traipsing ruins, and winding through elaborate museum corridors and spending hours trying to see every possible corner of a city that refuses to show itself fully, bearing the complaints and (sometimes) death threats from my family who just wanted to sit on the beach and get sand in crevices where sand was never meant to be and swallow half a gallon of sea water instead of reaching a 30k step count and having the mental image of the location impressed so tightly onto the insides of their eyeballs that it never leaves them. Because when I’m on the flight home I want to feel changed.

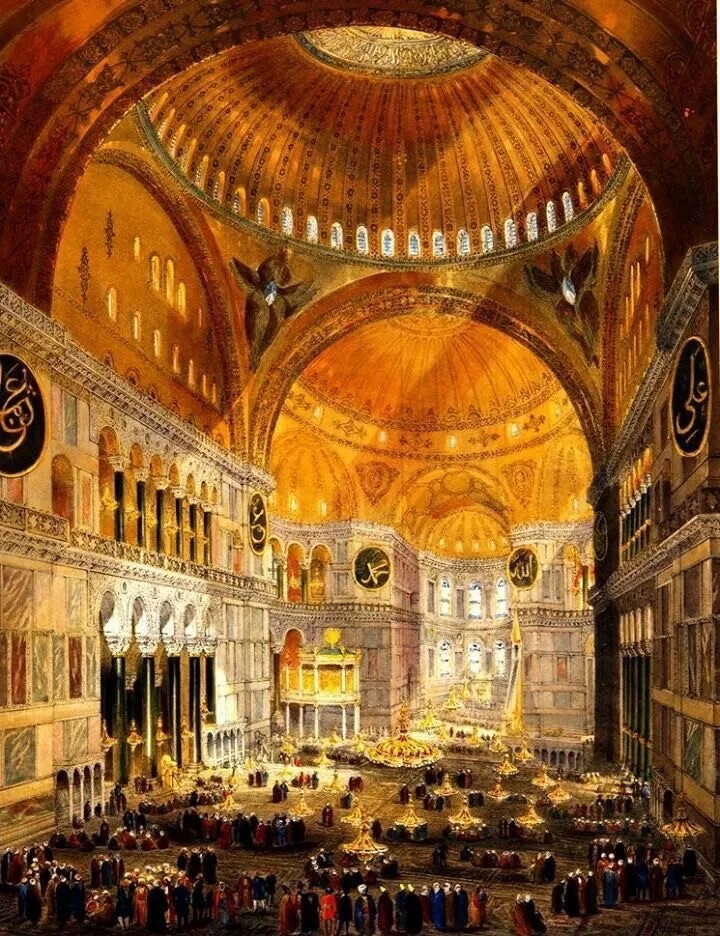

This level of conjuring, of imagination, of lifting something more from the concrete reality of my travels is a remnant of me being an extremely bookish child with an alarmingly active imagination, and very much why I’ve pursued a literature degree (not merely because I love to hear myself talk). Just as I have always loved travel, I have also loved the fictions that come tied with it. When I went to Istanbul when I was nine, I imagined myself as a princess in Topkapi palace, one of many memories and imaginings that became more tangible and valuable than the physical souvenirs of my week away.

And of course, to write about early modern Istanbul brings us face to face with the Ottoman Empire, which my Turkish friend remains constantly baffled as to why Turkish and Pakistani Muslims basically glorify the empire. I have to explain that yes I am researching the Ottomans, but this is not a fetishisation of Turkish history. Its more that I have to work within the realms of English fetishisation of Islamic lands and to do so, I am cornered into the early modern English box labelled ‘Islam’, whilst the Mughal, Safavid and far-east Asian study of the Islamic world falls out of the critical scholarly landscape.

I thus initially set out to write about travel to the Islamic world, with ambitions to bring Islam to my extremely white and Christianity-centred degree—this brings us to the more immediate impetus of my topic, finding a space for Islam in the parameters of my Cambridge degree. Before starting university, I knew what sort of world I was stepping into—outside the bubble of East London, Cambridge was the first time I realised I am actually a minority and the degree was literally English Literature, as in literature written in and about England, a space that I was only represented in as the non-human barbarian Muslim in the medieval romance or the oppressed Eastern damsel grateful to be rescued by a European sailor on the renaissance stage. So, my attempt was my chance to not analyse the Christian subtext in every weekly essay, but to talk about Muslims and POCs other than the ones that less often slip through the cracks, but become ugly cracks themselves, a flawed, less-than mirror of their European literary counterparts.

In this, I have felt that I have become a sort of mental traveller through my readings of 16th and 17th century travelogues of Cairo and Cyprus, but also Jaffa, Jerusalem and Gaza– which were highly frequented destinations for European travellers (it seems the West has a deliberately short memory). I am also a voyager inward, as is inevitable with literature. These mental journeys have taken me back to my own travels to a medieval Ottoman town in rural Bosnia, to the ruins of Hadrian’s Gate in Antalya and the remains at the Palatine Hill in Rome. They conjure other memories too: of learning about Muslim Spain in Primary School and later on a trip to Andalusia, and my A-Level History class, where so much of my imagination and fascination came to life.

It is in this amalgam that I am attempting to distill words—a project that increasingly seems impossible with the amount I always have to say, and the number of angles—intellectually and emotionally–I am trying so hard to imbue into a word document. I am thus attempting to superimpose onto my dissertation a mental Rihla—an intentionality beyond the impending deadline, to navigate this with intentions of recording not only the journeys 400 of years ago, but to trace and find the destination of the journeys throughout my life that have led me to this topic.

Indeed, the Prophet Muhammad (SAW) said:

‘Whoever takes a path upon which to obtain knowledge, Allah makes the path to paradise easy for him.’

-Sahih At-Tirmidhi

I hope you’ve enjoyed my words,

Zaynub<3